- Home

- Vanessa Able

Never Mind the Bullocks

Never Mind the Bullocks Read online

Praise for

Never Mind the Bullocks

Terrific and terrifying in equal measure: a life-affirming,

death-welcoming journey around the world’s most

dangerous roads in a wheeled toaster oven.

Tim Moore, author of Do Not Pass Go, Gironimo! and

French Revolutions

Vanessa is a gem – her writing is as effervescent and

refreshing as diving naked into a lake of champagne.

Olly Smith, TV presenter and author

The proverbial English dry wit.

Time Out

Travelling has never been this tough, never been this

enjoyable and entertaining as Able takes you on a

remarkable journey of humour through her scathing

comments and lucid writing… A hilarious book, from an

author that pulls no punches.

Postnoon

Vanessa Able is doggedly intrepid, deliciously acerbic, keenly

inquisitive and quite possibly mental.

Jaideep VG, Time Out India

A witty account of riding the Nano over 10,000km across

India, braving dust and grime, risking accidents and

flouting driving rules.

Livemint India

Able’s fight through fluctuating spirits, near-breakdowns,

interspersed with spurts of joy, influenced by a combination

of factors often beyond her control, is downright

inspirational.

Moneylife

An excellent and entertaining book.

Metrognome

Fluent and laced with, well, British-style humour. She

dispenses with political correctness and is blunt about horns,

headlights, hierarchies, stares, cops and toilets.

Business Standard

The book is an enjoyable read… this beautifully

narrated travelogue.

Businessworld

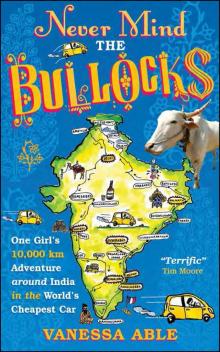

Never Mind THE BULLOCKS

One girl’s 10,000 km adventure around India in the world’s cheapest car

VANESSA ABLE

First published by

Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2014

3–5 Spafield Street

20 Park Plaza

Clerkenwell, London

Boston

EC1R 4QB, UK

MA 02116, USA

Tel: +44 (0)20 7239 0360

Tel: (888) BREALEY

Fax: +44 (0)20 7239 0370

Fax: (617) 523 3708

www.nicholasbrealey.com

© Vanessa Able 2014

The right of Vanessa Able to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-85788-612-2

eISBN: 978-1-85788-928-4

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

For the Ghost who came alive

CONTENTS

Start me up – Bagging the £1,000 car

1 Trial by Rush Hour – Girl Meets Traffic

Mumbai

RULE OF THE ROAD #1: THERE ARE NO RULES

2 Take-off – Down the NH66

Mumbai to Nagaon

3 Round the Bend – Defining Sanity, Osho Style

Pune

RULE OF THE ROAD #2: PUKKA PROTOCOL

4 The SH11T – Lost in Maharashtra

Kolhapur to Arambol

5 Anarchy on the NH7 – The Central Badlands

Hampi to Bangalore

RULE OF THE ROAD #3: HORN OK PLEASE

6 Mister Thor – Girl Meets Boy

Bangalore

7 Pedal to the Metal – The Hills of the Nilgiris

Mysore to Fort Kochi

RULE OF THE ROAD #4: FULL BEAMS OR BUST

8 Southern Comfort – A Swami’s Words of Wisdom

Kanyakumari to Tiruchirappali

9 Divine (Car) Insurance – Consecration and Catastrophe

Pondicherry

RULE OF THE ROAD #5: LEARN AT EVERY TURN

10 Paradise Beach – Finding Eden in Little France

Pondicherry to Chennai

11 Smart Car – More for Less for More

Hyderabad

RULE OF THE ROAD #6: STAY SAFE

12 O-R-I-S-S-A – Pastoral Paradise and X-rated Architecture

Bhubaneswar to Konark

13 Road Rage – Fear and Loathing in the Red-Hot Corridor

Bodh Gaya

14 The Raj by Car – Mr Kipling and the Henglish Drizzle

Nainital to McLeod Ganj

RULE OF THE ROAD #7: DON’T DRIVE (TOO) SILLY

15 Deflated in Delhi – How Not to Deal with a Blowout

New Delhi

16 One for the Road – A Right Royal Knees-Up at the Maharaja’s Table

Omkareshwar to Mumbai

RULE OF THE ROAD #8: MIND THE BULLOCKS

Starting Over – From Nano to Pixel

Epilogue

Notes

Acknowledgements

START ME UP – Bagging the £1,000 car

Let me get this straight: you’re planning to drive all the way around India in a Tata Nano?’ Naresh Fernandes, editor of Time Out Mumbai, asked me in a voice that sounded like disappointment. ‘Are you going to be planting lots of trees in your wake to compensate for the emissions?’

It was not the reaction I had hoped for. I sat across from him in his office, pathologically thumbing the retractor button of my biro and thinking of something witty to dredge me out of the mire of his opinion.

‘Umm, not exactly. No trees. But it is a fuel-efficient car, so I doubt it’ll cause too much… damage…’

‘Oh. Is it electric?’

‘No.’

‘Hybrid?’

‘No.’

‘Diesel?’

‘No. But it goes a fair distance per litre.’

‘How far?’

Folding under the pressure of the interrogation, my brain knocked random numbers around before drawing a blank and retreating with a whimper into the dank warren of its own inadequacy.

‘I’m not sure exactly,’ I said, trying to mask my inner dullard with an unconvincing veneer of cockiness, ‘but I know it’s a lot.’

‘What’s your route?’

‘A big circle around the country. Going south first. 10,000 kilometres.’

‘Why 10,000?’

‘Um. It’s a challenge?’

The chat was not going as planned.

I had come to Time Out Mumbai as part of a media outreach strategy intended to generate a level of hype and enthusiasm among the press similar to the one aroused in my loyal circle of support (namely my mum and my two best friends). I didn’t exactly imagine being drowned by a press tsunami, but I thought at least a little corporate nepotism might come into play with Naresh, given that I was a former Time Out editor myself. But this particular fish wasn’t in the least impressed by my plan and was most certainly not biting.

What I was too embarrassed to tell Naresh was that what had really drawn me to the Nano was one of my less virtuous traits, namely my limitless capacity for being motivated by

a bargain. The car recently launched by Tata Motors – the company that had bought Jaguar Land Rover in 2008 – was officially the world’s cheapest, and as such it had me at first sight: a hopeless sucker for marketing campaigns aimed at hopeless suckers bent on expanding their collection of easy electronic comestibles, I immediately added the vehicle (four doors, two cylinders and 624 cc of oomph, which, I was vaguely aware, was tantamount to a motorbike with a roof) to the tally of delectable gadgets that were within reach of my credit card limit. It was the first time a new car had ever featured on that list, an event that inspired in me the warm rush of consumer anticipation.

‘What’s that, a Smart Car?’ asked my mum, squinting into the screen of my laptop.

‘Actually, Mum, it’s a Tata Nano. It’s the cheapest car in the world.’

‘I haven’t seen any about.’

‘That’s because we don’t have them here in Jersey.’

‘So where are they, then?’

‘India.’

‘India?’

This was the other part of the story. Although Tata had plans for releasing the Nano globally at some point in the future, for now the only place one could buy a model was in India. I was gutted: it had never occurred to me that, unlike laptops and phones, cars were not altogether international products.

‘So, yeah. I’m thinking of going over there to get one. Drive it around a bit.’

My mother didn’t flinch. In the last few weeks she had become accustomed to my reactionary rhetoric, a horrible regression in behaviour that followed my move back home after the sticky end of a four-year relationship.

‘Haven’t you been to India enough? What about getting a job instead?’

With the vexation of a vilified teen, I inhaled and slowly reeled off the same speech I had been laying on my parents for the last decade, namely that freelance travel writing was a job and a noble one at that. If she had the impression that my time was not sufficiently consumed by the pursuit, it was only because the publishing world was currently in crisis and work was thin on the ground. I had come here to my childhood home – nay, refuge – on the Channel Island of Jersey as an interim measure, to consider my future in the light of the current global climate and to decide what to do next. And whatever that was, I indignantly assured her, it would certainly not involve any job of the nine-to-five variety. I was a free soul, a wanderer; a leaf that floated in the breeze and submitted hotel and restaurant reviews to paying publications. My wings might have been clipped, but I wasn’t about to let that stop me.

‘Anyway, it’s about to be my Jesus Year,’ I reminded my mother.

‘Your what?’

‘My Jesus Year. Thirty-three. It’s when you make things happen in your life. When you make decisions and change things.’

‘Why not make it the year you decide to finally enter a legitimate workforce?’

I opted not to comment.

‘Besides, Jesus died when he was thirty-three. That’s so morbid.’

Mum was right, as she often is, in her assertion that I’d been to India a lot. And that a proper paying job would be something of enormous benefit. This was true: but since I’d started thinking about the Nano, a thought process that coincided with other ideas of immediate escape from the rock of my birth that was now holding me emotional prisoner, I had become possessed by the idea of returning to India. A decade earlier, it had been the land of opportunity for me: a paradise for the youthful, adventurous and relatively broke. It was an anarchic, volatile, often squalid place where my conceited young soul could play out the illusion of influence with as little as a few quid in my back pocket. A world of easy drugs and full moon parties set against a blurred and (for me then) only fleetingly interesting background of social hardship, where for the western traveller hippie type virtually anything could be made possible for the right price, and that figure was a fraction of what it was back at home.

Would those things really still hold any appeal? I knew I was definitely a few years over that level of decadence, but the urge to explore India was still in my veins. My savings account contained several times more than it ever had during my student days when the vacation coffers were only scantly furnished with the proceeds from a job pulping oranges at a doomed juice bar on Charing Cross Road. Now I had the kind of money that could buy me three months in India. I could, I reasoned, purchase myself one of these cheap cars and take it all the way around the country on the drive of a lifetime. What better way, I mused, to take on newly single life and embark on another, more daring chapter?

While I was indulging in these fantasies, hype around the Nano was ballooning globally, as the international media caught on to what the car actually meant in a country with a booming economy and a ballooning new middle class. USA Today echoed the popular opinion that the car ‘may yield a transportation revolution’, while Time magazine pegged it as ‘one of the most important cars ever designed’. ‘Indian streets may never be the same again,’ declared the BBC, and Newsweek asserted that the Nano was ‘changing the rules of the road for the auto industry and society itself’. But it was the Financial Times’ claim that the Nano encapsulated ‘the dream of millions of Indians groping for a shot at urban prosperity’ that really caught my imagination. This was my chance to partake in what was destined to be legend.

I was sold. All that remained was to figure out how to get my hands on one.

‘Hello! Mr Shah?’ I yelled into my computer. ‘I’d – like – to – buy – your – Nano!’

‘Something something Nano?’ Mr Shah shouted back.

‘Yes, your Nano! I want to buy it! How much for your Nano, Mr Shah? Your – Nano – that – is – for – sale?’

Silence, followed by a low churning noise.

It turned out that trying to buy the most wanted car in India off a bloke in Mumbai from an island in the English Channel was not as easy as I had anticipated. Spurred on by an internet ad I had come across earlier, I had dialled Mr Shah with the aim of coming to some agreement about the sale of his car, and in the hope that he might take credit cards. But I soon discovered that such high-stakes negotiations were not suited to debilitated internet telephony. All I could hear from my laptop speaker was a series of crackles and the voice of a man-bot who sounded like he was trying to physically project his voice 9,000 km into my ear.

‘Mr Shah? How much is it, the car?’

‘Something something two-lakh four.’

I had no idea what he was talking about. ‘Sorry, could you repeat that, please?’

There was no response and I couldn’t tell if he’d heard me. I gave my laptop a caustic shake as though jiggling it might help clear the crud that was blocking the line or the satellite beam somewhere between me and Mumbai. But with Mr Shah’s voice still only coming through in barely fathomable fits and starts, my patience expired and I finally hung up to rethink my strategy.

When Tata launched the Nano at the Delhi Auto Expo back in 2008, it was not yet ready to go on the market. Due to a controversy surrounding the acquisition of land for its proposed factory in West Bengal, production of the car had been delayed. To keep buyers interested, Tata nonetheless opened the brand up for business and began to take orders. There was a deluge towards dealership offices, as forms were hastily filled out and hefty deposits paid. Around 200,000 orders were placed before Tata decided it would be best to close the lines, as the number was higher than it could realistically produce in the coming months. It eventually accepted half of the orders, which it chose through a lottery, and pledged that the cars would all be delivered by October 2010. In a time of global recession, 2010 was still looking bright for India’s economy, which had been on the rise ever since the liberalization of the country’s financial system in 1991. The advent of the Nano was just another symptom of the boost in trade and industry that was providing hundreds of thousands of people with their first taste of material might, and, for now at least, it seemed they all wanted to buy the same car.

So in J

anuary 2010, nine months before the delivery deadline, it transpired that simply snapping up a Nano was an impossible task. Dealerships were only distributing the car to people on Tata’s waiting list, and it was predicted that new buyers might have to hold out for a whole year before getting their hands on one.

As far as I was concerned, this wouldn’t do. I had made up my mind to leave Jersey and circumvent India in the World’s Cheapest Car, and every day I spent getting narky with my mum, or huffing when my dad asked me to close the garage door, was another day of lessening self-worth. In order to bag a Nano, I realized I would need an accomplice in India; a person on the ground, a local, a savant, someone who could pull strings and get me what I damn well wanted. I needed an Indian genie of sorts, so I called on the only person I knew who could fulfil that role, who also happened to be the only person I knew in India at the time. My saviour was Akhil Gupta, a friend of my American cousin who I had met some years ago at a birthday party in Vermont. All I really knew about Akhil was that he lived in Mumbai and was the chairman of a private equity firm called Blackstone India. Our link was tenuous to say the least, so it was with some hesitation that I sent him an email one day out of the blue asking if he could help me buy a car.

Gentleman and inveterate yes-man that he is, he didn’t flinch and responded immediately in the affirmative, as though I’d asked him to pop round the corner for a pint of milk. A few days later, however, he came back to me with grim tidings. After some extensive research, he confirmed that it was not possible to buy a Nano at a dealership anywhere in India.

The project looked on the verge of being shelved, and Akhil was showing signs of relief. He tactfully put some more sensible recommendations on the table: a Toyota Innova, he suggested, would be a far more suitable vehicle in which to tour India, and for £350 a month I could hire the car and the driver. Clearly concerned for my safety, Akhil outlined the following reasons in neat bullet points as to why I should definitely not attempt to cross India in a Nano:

• Nano is not meant for highway driving.

Never Mind the Bullocks

Never Mind the Bullocks